|

| Source |

General Winchester and Whitmore Knaggs Surrender To Blue Jacket

European Union laws require you to give European Union visitors information about cookies used on your blog. Note: I'm not savvy enough to know about blog cookies; if there's a concern on your part, it's probably best not to visit my pages.

|

| Source |

|

| Source |

| Source |

The day after his hearing of the Declaration of War against Great Britain, Captain Gratiot, being then at St. Louis visiting his parents during his leave of absence, immediately proceeded to Washington to ask for active service; and was at once appointed Chief Engineer of the North Western Army, with orders to stop en route at Pittsburg to aid in the preparation of ordnance and ordnance stores for General Harrison's forces then in the field. Not till November 1812, could Captain Gratiot and his escort of 300 men move, with the heavy train of twelve pieces of artillery and two hundred loaded vehicles, to Lower Sandusky through an almost trackless wilderness where a wheel had never rolled. After persistently overcoming winter's cold bad roads want of forage and numerous other difficulties, he delivered, January 5, 1813, his whole charge without even the loss of a bullet, to the Commander-in-Chief, who, soon after Winchester's defeat, directed Gratiot to join him without delay at Maumee Rapids.

| Source |

General Winchester [and his Headquarters at the River Raisin].

|

| Source |

| Source |

Darnell's Journal, A journal containing an accurate and interesting ... included the entry below that referred to the Siege of Fort Wayne:

See a previous post from Darnell's Journal here.

Upon this site stood Chief Roundhead's Wyandot Indian village. Roundhead, or Stiahta, was celebrated for his capture of American General James Winchester during the War of 1812.

| Source |

| Source |

| Source |

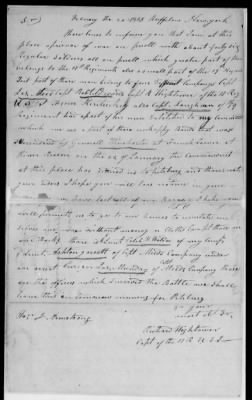

General Winchester's rebuttal "concerning charges of neglect and military incompetency during the course of the Raisin campaign (directly mainly by Robert McAfee in his book published in 1816)" can be found here.

"Getting supplies to the army on the western frontier of Indiana, Ohio and Michigan in 1812 was a difficult business."

Letter from John Richardson to his Uncle, Captain Charles Askin.

Amherstburg, 4th February, 1813. My Dear Uncle,—

You have doubtless heard ere this of the engagement at the River Raisin on Friday, the 22nd inst. (ult.)f however, you may probably not have heard the particulars of the business, which are simply these: On Monday, the 18th, we received information that the Americans, under the command of General Winchester, after an obstinate resistance, had driven from the River Raisin a detachment of Militia under Major Reynolds (also a party of Indians) which had been stationed there some time. That they had sustained great loss from the fire of our Indians, and from a 3-pounder, which was most ably served by Bombardier Kitson (since dead), of the R.A.

On Tuesday part of our men moved over the river to Brownstown, consisting of a Detachment of R. Artillery, with 3 3-pounders and 3 small howitzers, Capt. Tallon's Company (41st Regt.), a few Militia, and the sailors attached to the Guns. An alarm was given that the enemy were at hand. The Guns were unlimbered and everything prepared for action, when the alarm was found to be false.

On Wednesday the remainder of the army joined us at Brownstown, where (including Regulars, Militia, Artillery, Sailors and Indians) we mustered near 1,000 men. We lay, this night, at Brownstown. Next day the army commenced its march towards the River Raisin and encamped, this night, at Rocky River, which (you know) is about 12 miles beyond Brownstown and 6 on this side the River Raisin. About two hours before day we resumed our march. On Friday at daybreak we perceived the enemy's fires very distinctly—all silent in their camp. The army drew up and formed the line of battle in 2 adjoining fields, and moved down towards the enemy, the Guns advanced 20 or 30 paces in front and the Indians on our flanks. We had got tolerably near their Camp when we heard their Reveille drum beat (so completely lulled into security were they that they had not the most distant idea of an enemy being near), and soon after we heard a shot or two from the Centinels, who had by this time discovered us. Their Camp was immediately in motion. The Guns began to play away upon them at a fine rate, keeping up a constant fire. The Americans drew up and formed behind a thick picketing, from whence they kept up a most galling fire upon our men, who, from the darkness of the morning, supposed the pickets to be the Americans; however, as it grew lighter, they discovered their mistake, and advanced within 70 or 80 paces of the pickets, but finding that scarce one of their shots took effect, as they almost all lodged in the fence. Being thus protected from the fire of our men they took a cool and deliberate aim at our Troops, who fell very fast, and the most of the men at the Guns being either killed or wounded, it was thought expedient to retire towards the enemy's left under cover of some houses. I was a witness of a most barbarous act of inhumanity on the part of the Americans, who fired upon our poor wounded, helpless soldiers, who were endeavouring to crawl away on their hands and feet from the scene of action, and were thus tumbled over like so many hogs. However, the deaths of those brave men were avenged by the slaughter of 300 of the flower of Winchester's army, which had been ordered to turn our flanks, but wh.o, having divided into two parties, were met, driven back, pursued, tomakawked and scalped by our Indians, (very few escaping) to carry the news of their defeat. The General himself was taken prisoner by the Indians, with his son, aide, and several other officers. He immediately dispatched a messenger to Colonel Procter, desiring him to acquaint him with the circumstance of his being a prisoner, and to intimate that if the Colonel would send an officer to his Camp to summons the remainder of his army to surrender, he would send an order by him to his officer then commanding to surrender the Troops. Colonel Procter objected to sending one of his own officers, but permitted the General to send his aide (with a flag). The firing instantly ceased on both sides, and about 2 hours afterwards the enemy (460 in number) laid down their arms and surrendered themselves prisoners of war. A good many of our officers were wounded in the engagement, but none of them killed. The following is a list of them: R.A., Lt. Troughton (slightly); Seamen attached to the Guns, Capt. Rolette, Lt. Irvine, Midshipman Richardson (severely); 41st Regt., Capt. Tallon, Lieut. Clemow (severely); Militia, Inspecting F. Officer Lt.-Col. St George, Capt. Mills, Lt. McCormick, Paymaster Gordon (severely), Ensign Gouin (slightly), R. N. F. Regt, Ensign Kerr (dangerously); Indian Depart., Capt. Caldwell, Mr. Wilson (severely). This is as accurate an account as I can give you of the Engagement. I will now give you an account of my feelings on the occasion. When we first drew up in the field I was ready to fall down with fatigue from marching and carrying a heavy musquet. Even when the balls were flying about my

ears as thick as hail I felt quite drowsy and sleepy, and, indeed, I was altogether in a very disagreeable dilemma. The night before at Rocky River, some one or other of the men took my firelock and left his own in the place. It being quite dark when we set out from that place, I could not distinguish one from another. Enquiry was vain, so I was obliged to take the other (without thinking that anything was the matter with it). When we came to the firing part of the business I could not get my gun off. It flashed in the pan, and I procured a wire and worked away at it with that. I tried it again, and again it flashed. I never was so vexed—to think that I was exposed to the torrent of fire from the enemy without having the power to return a single shot quite disconcerted the economy of my pericranium; though if I had fired fifty rounds not one of them would have had any effect, except upon the pickets, which I was not at all ambitious of assailing like another Don Quixote. Our men had fired 4 or 5 rounds when I was called to assist my brother Robert, who was wounded, and who fell immediately, and which led me to suppose that he was mortally wounded. However, when he was carried to the doctors I found the poor fellow had escaped with a broken leg, which torments him very much, and it will be some time before he gets over it. I think it is highly probable we shall have a brush with the valiant Harrison, who is said to be at the Rapids of the Miami River, or near them. If so, I think we shall have tight work, as we have lost in killed and wounded in the action of the 22nd 180 men (exclusive of Indians). Pray remember me to my cousins, and, Believe me,My Dear Uncle,Yours affectionately,John Richardson. Mr. Chas. Askin, ) Queenston.

Fort Barbee was erected by Colonel Barbee near the west bank of the St. Mary's River, on the site of what afterwards became a Lutheran cemetary [sic], in the town of St. Marys.From The Ohio Country....

The necessity for additional roads and places for the protection of food and other military supplies being urgent, General Harrison returned to St. Marys, where he found the expected Kentucky troops. Colonel Joshua Barbee was instructed to build there an ample fortification, and storehouse within the stockades, which was named Fort Barbee.

Winchester's report of the enemy was received by Harrison at Fort Barbee September 30th, as was also a report from Governor Meigs of a strong force of the enemy opposing Winchester. The three thousand men then at Fort Barbee were at once started direct for Defiance, Harrison commanding in person.